Beyond the fame, beyond the money, beyond the followers, and even at times–beyond the glory–stands a stalwart in independent filmmaking, an auteur in global art that spans nearly three decades. A traveling cinéaste with the fervor of an intellectual activist, the focus of an academic scholar, and the passion of a renaissance musician lies a one–Raoul Peck, born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti–reared in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, educated in Berlin, Germany, and currently resides and works in the country of France. Not yet or ever will be a household name on varying continents but a much understood force in black, international cinema. Raoul Peck is one of the most important filmmakers alive today. In a world where over-saturation of media content and the redundancy of mainstream work has taken precedence in film and television industries worldwide–year after year, work after work Peck has delivered powerful, memorable filmmaking. He has risen to the pinnacle of top auteurs today simply upon the fact of his global relevancy. His work bridges the gap among three distinct continents–North America, Europe, and Africa. His tireless execution of delivery has gone beyond didactic tendencies or educational forums–it has raised a much marginal level of awareness into the profundity of a necessary voice.

Like all masters of their given craft Peck worked his way late in the ever-changing film industry that began with humble beginnings as a taxi driver in New York City and then as a freelance photographer and journalist up until he formed his award-winning film production. Along the way he educated himself on his place in a world from black Caribbean roots to a citizen of the African mainland. Establishing himself as an autodidact Raoul Peck found his mark behind the camera delivering the juxtaposition of real life in the context of cinematic dramas. Throughout his stellar film work Peck consistently carries his growing, niche audiences into disclosed corners of the world to piecemeal the nuance of troubled realities. We see this in his biopic film, Lumumba, centered on the fame Congolese freedom fighter. In the death scene that culminated the climax of the film, a poetic voice-over narration awakens the viewer spoken from the actual, gripping words of Patrice Lumumba himself–“…Don’t weep my love. One day history will have its say. Not the history they teach in Brussels, Paris or Washington, but our history. That of a new Africa….” Rarely, is Peck afraid to jump into the controversy of political strife and delve deep into the gray of troubled society and suck out all its marrow.

Consistency is a rare mark among the longevity of careers–in any industry today. Consistency is where Peck made his mark, his living, his impact, his legacy. Written scripts that bring forth absorbing, moving sentiments carries his movies’ leitmotifs with little to no moralizing involved. Gripping scenes of demise emotionally moves his audiences to places few movie creators dare to tread. We see the maim, bloody bodies in his movie, Sometimes in April, a lucid depiction on the Rwandan genocide starring Idris Elba. We are felt by the cracked debris and the pulverization of Haiti in ruins in the movie, Murder in Pacot. Both films brings for the the nuances of human bodies in the midst of poor, marginalized black societies. Peck’s signature touch is of quiet acknowledgment from the long, self-reflective commentary lucidly juxtaposed with scenic images of telling realism, the quiet reflection of profound points-of-views from varying soundbites and narration, and even the simple music touch that carries with it an emotion of sorrow and hope. In his documentary, Fatal Assistance, he speaks to his audience with a pan aerial camera shot of post-earthquake hit Haiti where blue tents map out the given landscape: “Who’s going to save us from our saviors?”

Raoul Peck’s passion and enthusiasm is what should carry all artists forward; all artists forwarding into limitless boundaries. Bent on uncovering and exposing truth in its barest form Peck’s camera visualizes poetic movements from symbolism back to nature in its honest form. Seeking to raise awareness on controversial and complex subject matter Peck’s scripts is written in a lucid manner told in a philosophical tangent yet grounded in realism. In his biopic documentary, Lumumba: Death of a Prophet (a precursor to his latter narrative biopic) the carrying question of Patrice Lumumba’s fate as his country’s independence leader is conveyed with the quiet build of a biographical account. We pierce through the complex dimensions of a newly independent country–DRC, through the eyes of such glorified yet misunderstood hero–evolving from staggered colonization to stark despotism. His question of Lumumba as the prophet of not only the Congo but of central Africa if not all of Africa in the awakening years of the early 1960s–should be our question as the viewer too.

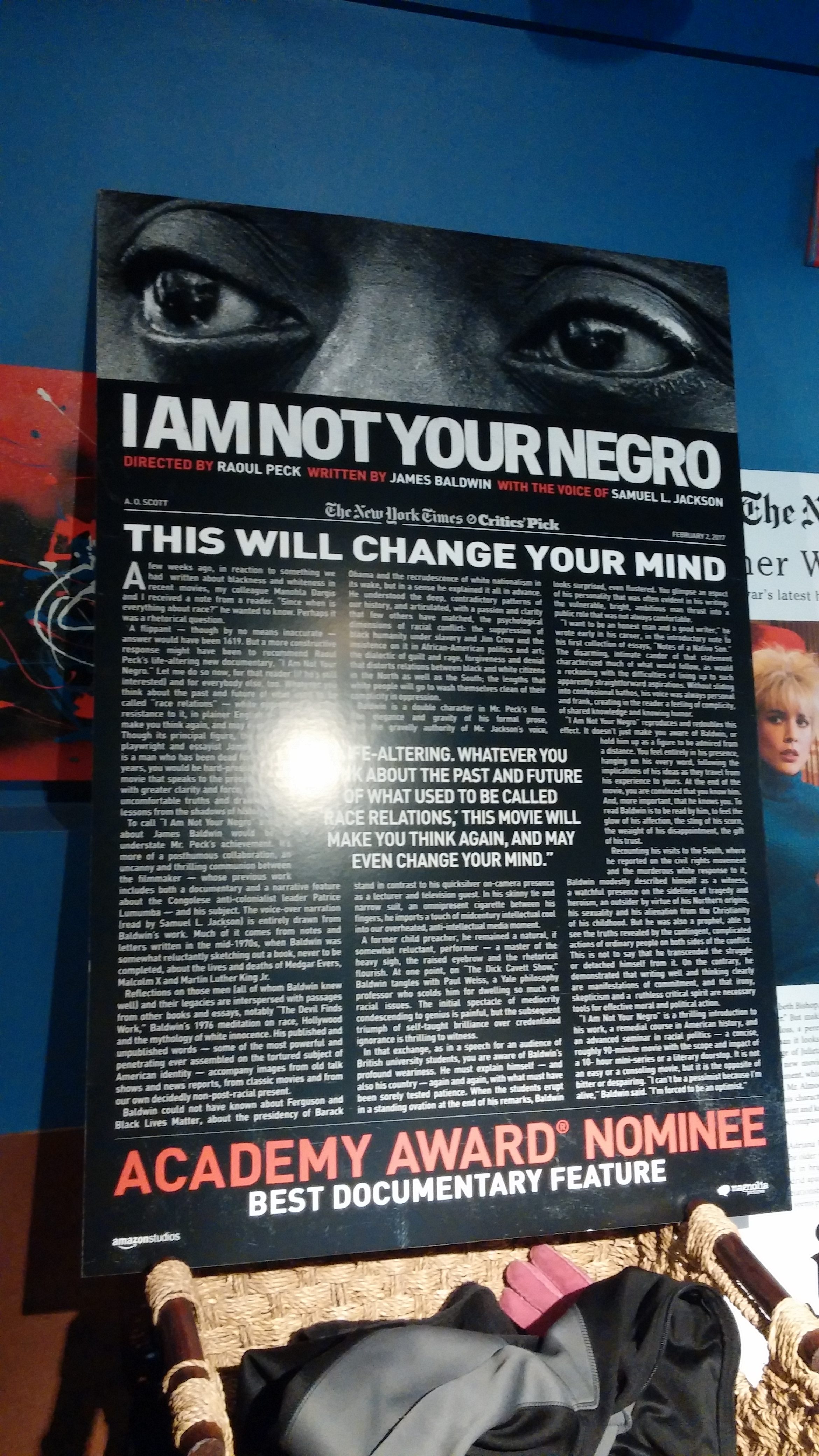

Peck’s gift to us as a master cinéaste shines once again in his latest Academy Award-nominated film, I Am Not Your Negro. Here, he challenges us and ultimately challenges himself to deconstruct through the deep wounding reality of modern racism laid out in the vision and eloquence of the fiery James Baldwin. No other filmmaker could’ve accomplished this task. This intriguing storytelling approach takes the deep subject matter of a James Baldwin commentary and life story into an understood context to an audience not familiar with his work. The film, written from an unpublished work of the passionate Baldwin and narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, guides the viewer in the intricate and contentious subject matter of American racism in the subsequent generation following the Civil Rights Movement. The documentary is constructed like a flowing arthouse, experimental piece where images of slaves, lynched bodies, Civil Rights icons are matched with and along movie snippets of African Americans portrayed in 1940s and 1950s-era Hollywood films. Delicately interwoven with James Baldwin interviews and lecture videos that illuminate the articulate brilliance of this seminal figure in modern black history, I Am Not Your Negro hits home the direct question (if not answer) to the destiny of the so-called “American experiment” as it relates to her growing and diverse racial demographic. With the subtlety of poetic lyrics from Baldwin himself portrayed with the lucid depictions of archival material we better appreciate the nuances that is race relations of the late 20th and early 21st century.

To that–we must thank Raoul Peck for such achievements.