My Top 20 Biographical Documentaries of All-Time

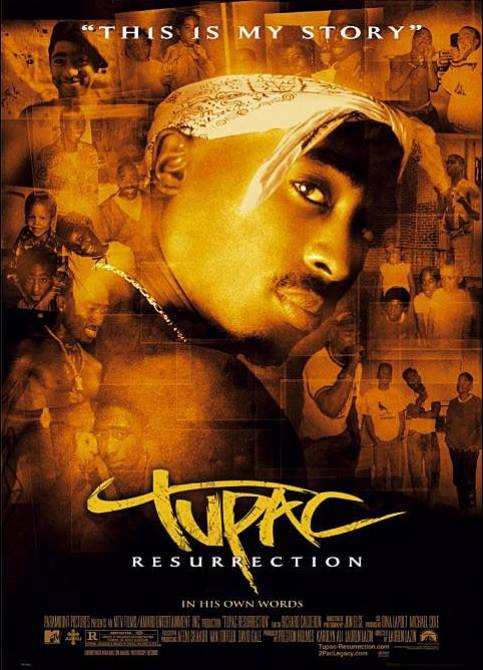

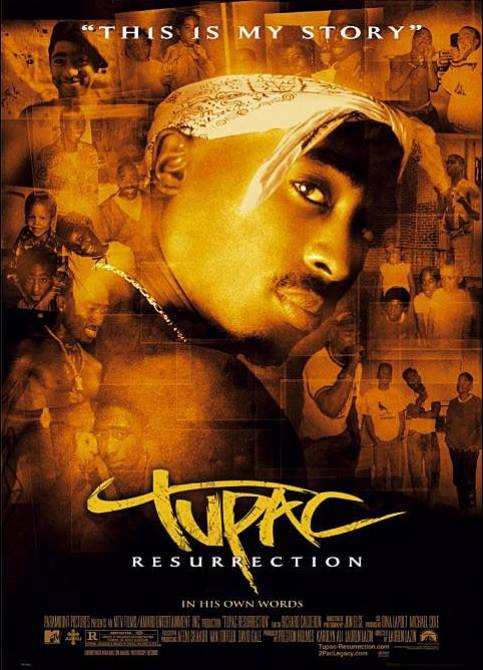

1. Tupac Resurrection – Lauren Lazin (2003)

Brilliant exposé conveyed in the mind and thoughts of the slain rapper as his story is being unraveled on screen. Can one really top a music biopic of Tupac Shakur telling his biography in his own words?

Brilliant exposé conveyed in the mind and thoughts of the slain rapper as his story is being unraveled on screen. Can one really top a music biopic of Tupac Shakur telling his biography in his own words?

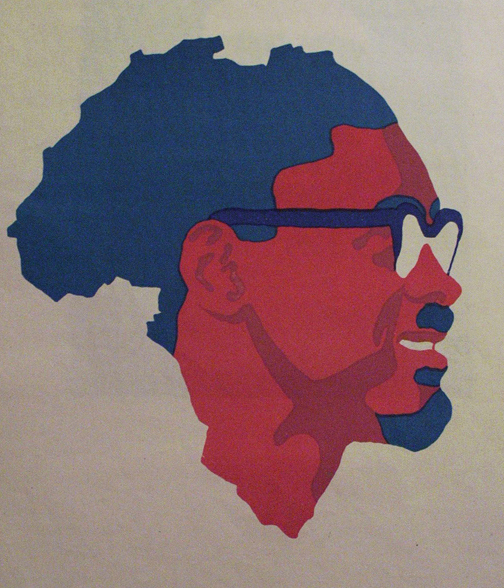

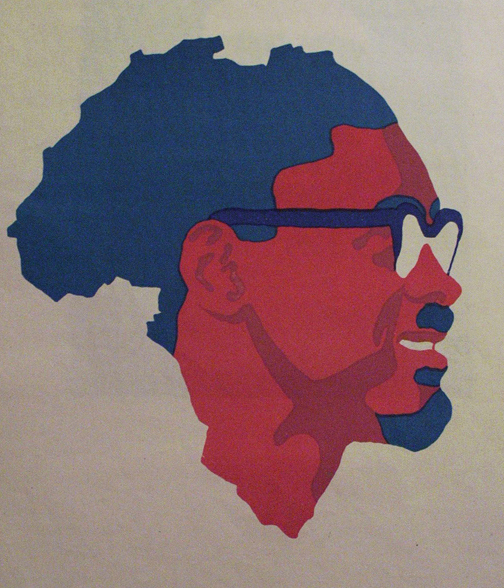

2. Lumumba: The Death of a Prophet – Raoul Peck (1990)

Poignant look into the renowned Congolese leader and his significant work for his country’s independence. Filmmaker Raoul Peck delivers an introspective look into the legacy and political mark Patrice Lumumba left on others. This narrative is delivered with little to no music as to not embellish any sentimentality on the biopic.

Poignant look into the renowned Congolese leader and his significant work for his country’s independence. Filmmaker Raoul Peck delivers an introspective look into the legacy and political mark Patrice Lumumba left on others. This narrative is delivered with little to no music as to not embellish any sentimentality on the biopic.

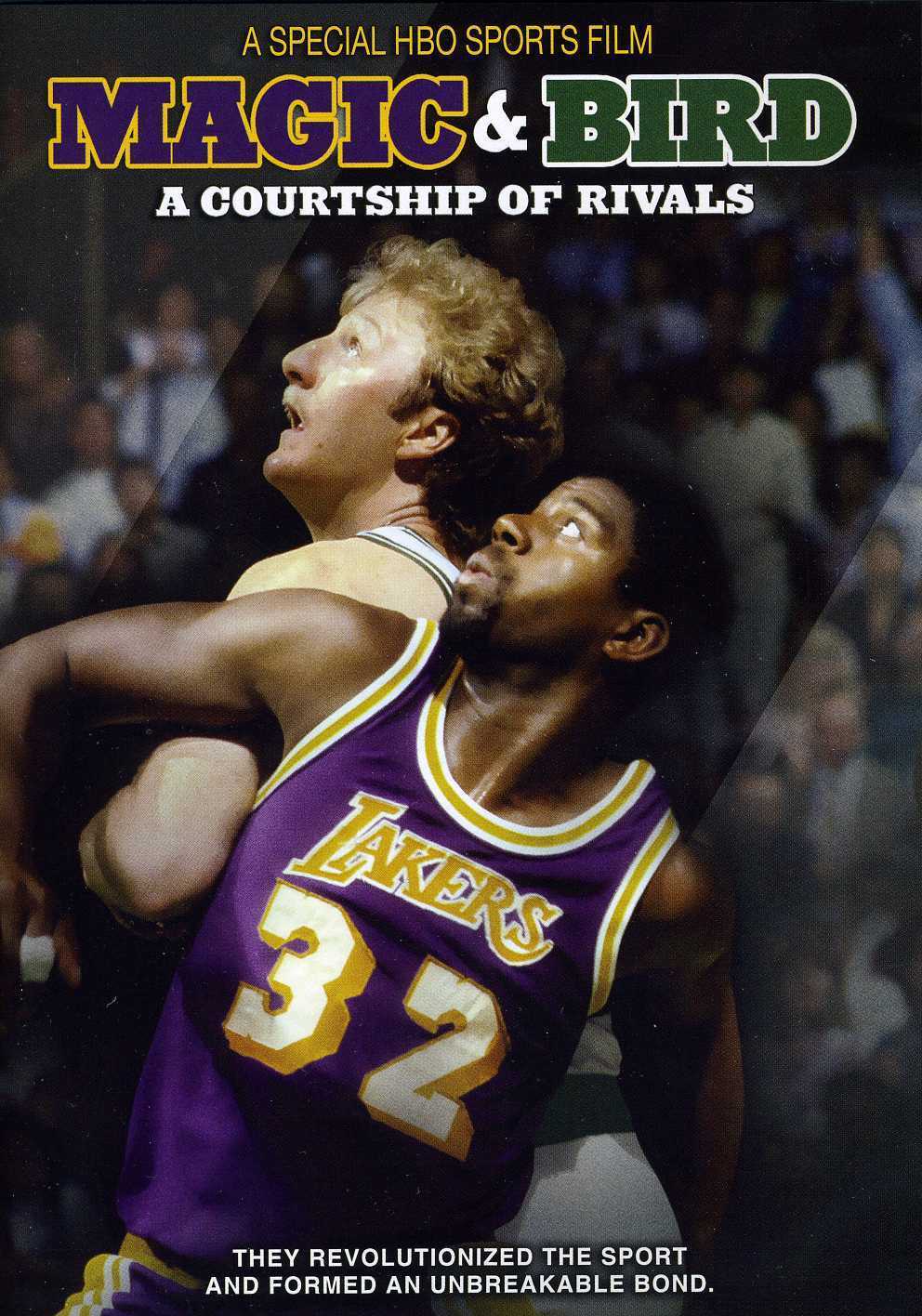

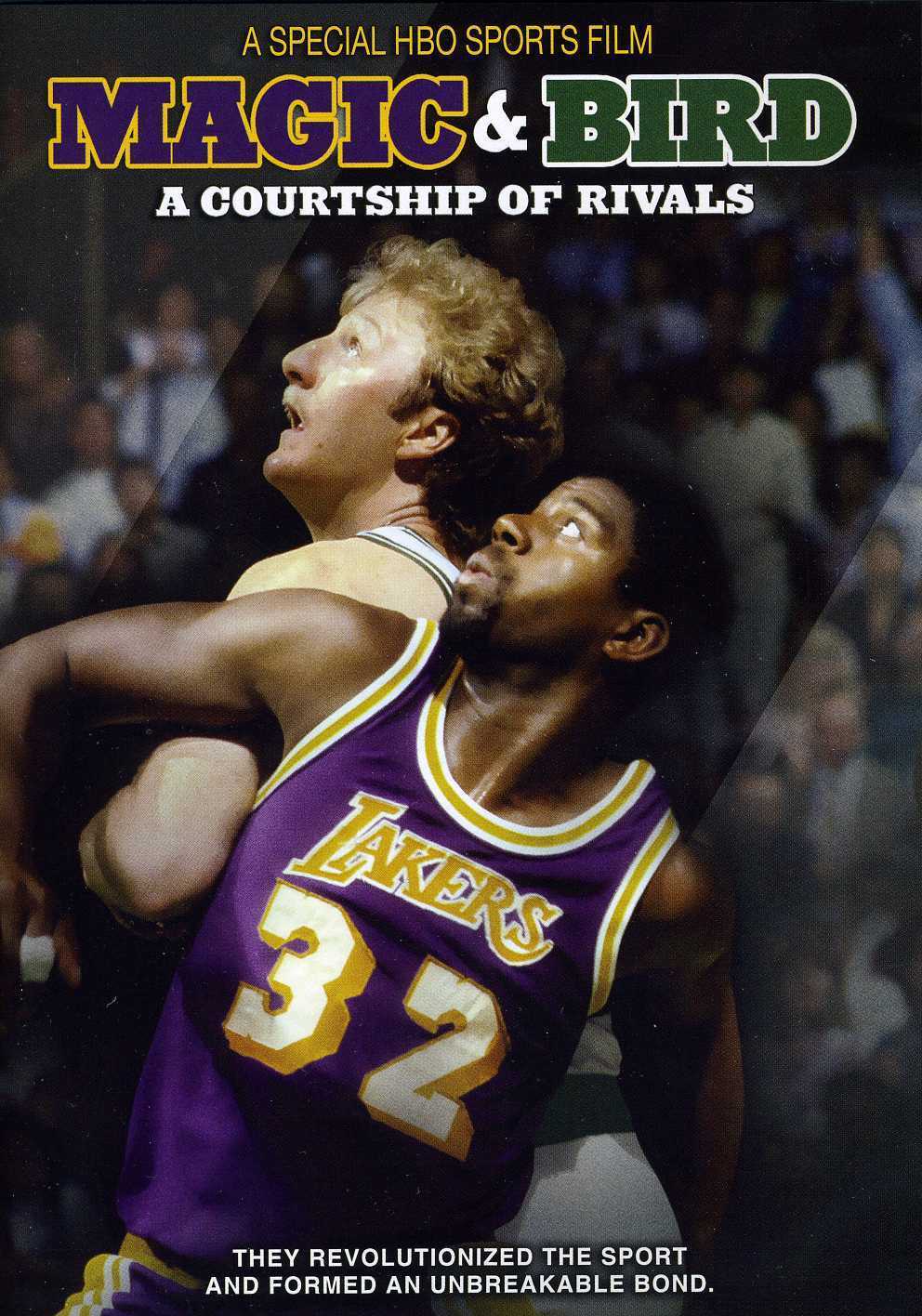

3. Magic & Bird: A Courtship of Rivals – Ezra Edelman (2010)

Easily could be considered a homage to two Hall of Famers who together saved the NBA in the 1980s. Instead, we have a profound sports film of polar opposite stars at the time of their reign.

Easily could be considered a homage to two Hall of Famers who together saved the NBA in the 1980s. Instead, we have a profound sports film of polar opposite stars at the time of their reign.

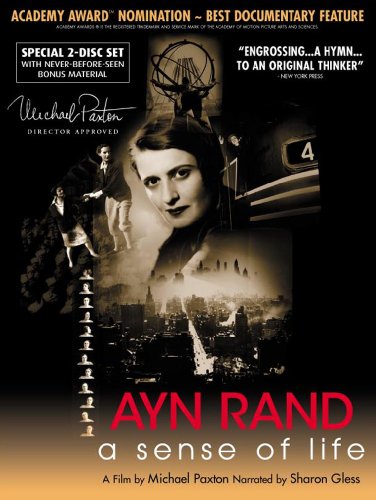

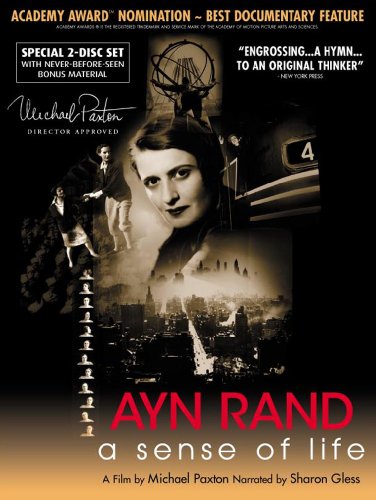

4. Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life – Michael Paxton (1996)

A uniquely deep biopic on one of the most polarizing figures of the 20th century. Director Michael Paxton takes us through the life and times of Ayn Rand with a honest touch covering all her dramatic life events and characteristic nuances that made her who she is.

A uniquely deep biopic on one of the most polarizing figures of the 20th century. Director Michael Paxton takes us through the life and times of Ayn Rand with a honest touch covering all her dramatic life events and characteristic nuances that made her who she is.

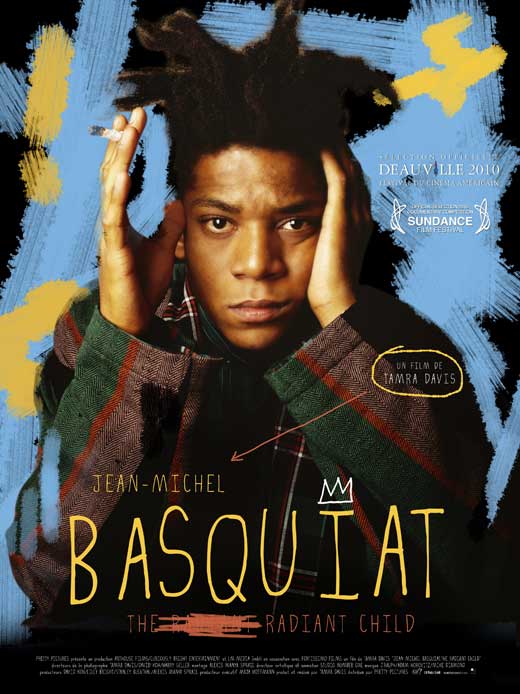

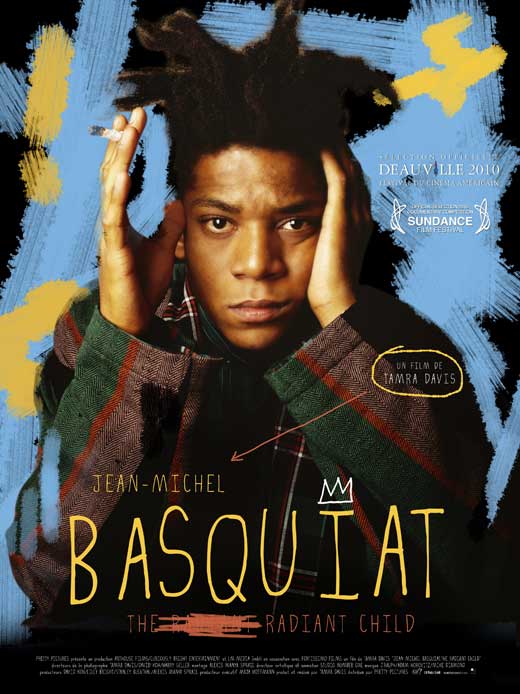

5. Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child – Tamra Davis (2010)

A fun, experimental biographical film that lucidly depicts the story of the famed artist from his humbling beginnings, pinnacled career success, and untimely death. It is enriched by depicting the very environment where the story unravels–NYC–and from those who knew him best.

A fun, experimental biographical film that lucidly depicts the story of the famed artist from his humbling beginnings, pinnacled career success, and untimely death. It is enriched by depicting the very environment where the story unravels–NYC–and from those who knew him best.

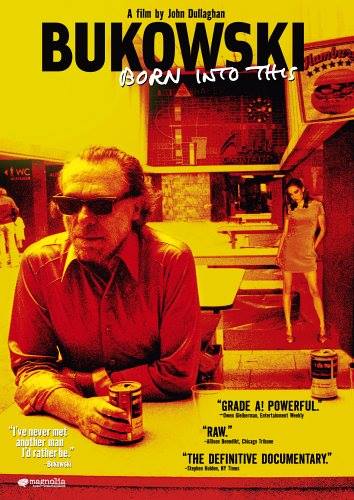

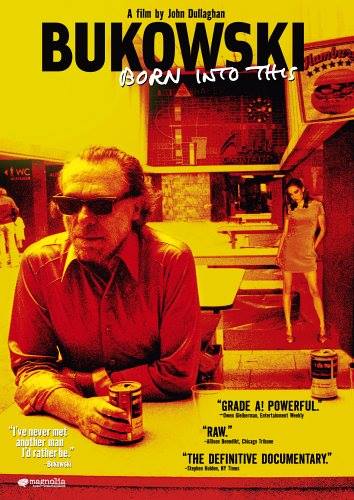

6. Bukowski: Born Into This – John Dullaghan (2003)

Raw and thought-provoking portrayal of the famed and often misunderstood writer–which perfectly sums up the legacy of Charles Bukowski. This documentary dispels any of the misunderstandings to Bukowski and lets the story unravel as we walk in the footsteps of his life with limited commentary and the best picked archival material found.

Raw and thought-provoking portrayal of the famed and often misunderstood writer–which perfectly sums up the legacy of Charles Bukowski. This documentary dispels any of the misunderstandings to Bukowski and lets the story unravel as we walk in the footsteps of his life with limited commentary and the best picked archival material found.

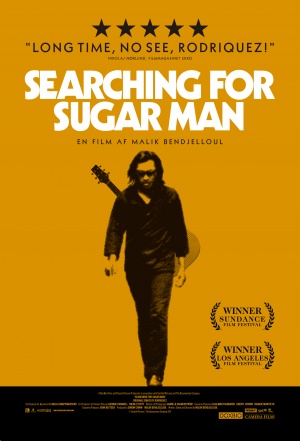

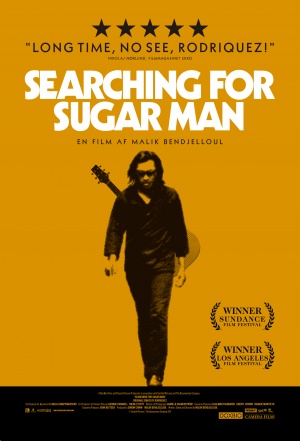

7. Searching for Sugarman – Malik Bendjelloul (2012)

A different approach to a biographical film of a musician which reveals over time to us the mystery of the subject himself. Through the use of symbolic imagery, lyrical content, and an investigative approach this documentary reveals more to audiences than just a single narrative of a forgotten musician but rather the impact of music on political movements and the valuing of fame and talent across countries.

A different approach to a biographical film of a musician which reveals over time to us the mystery of the subject himself. Through the use of symbolic imagery, lyrical content, and an investigative approach this documentary reveals more to audiences than just a single narrative of a forgotten musician but rather the impact of music on political movements and the valuing of fame and talent across countries.

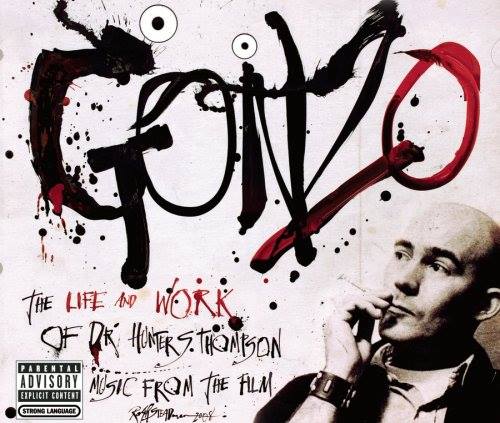

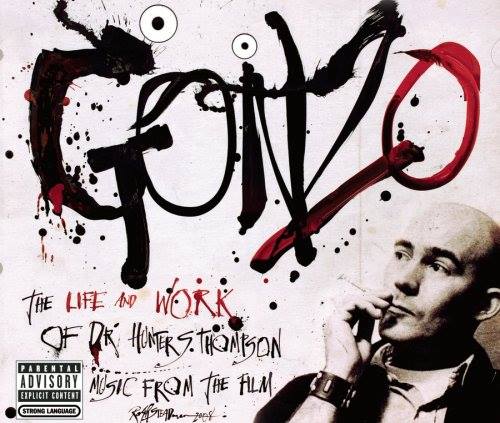

8. Gonzo: The Life and Work of Hunter S. Thompson – Alex Gibney (2008)

Fascinating piece of documentary film work on an enigmatic pop culture icon. No other filmmaker could’ve accomplished such a thorough and challenging task in lucidly capturing the character and work of gonzo journalist-writer Hunter S. Thompson. With interviews with President Jimmy Carter and narrated by actor Johnny Depp Alex Gibney puts together a masterpiece film.

Fascinating piece of documentary film work on an enigmatic pop culture icon. No other filmmaker could’ve accomplished such a thorough and challenging task in lucidly capturing the character and work of gonzo journalist-writer Hunter S. Thompson. With interviews with President Jimmy Carter and narrated by actor Johnny Depp Alex Gibney puts together a masterpiece film.

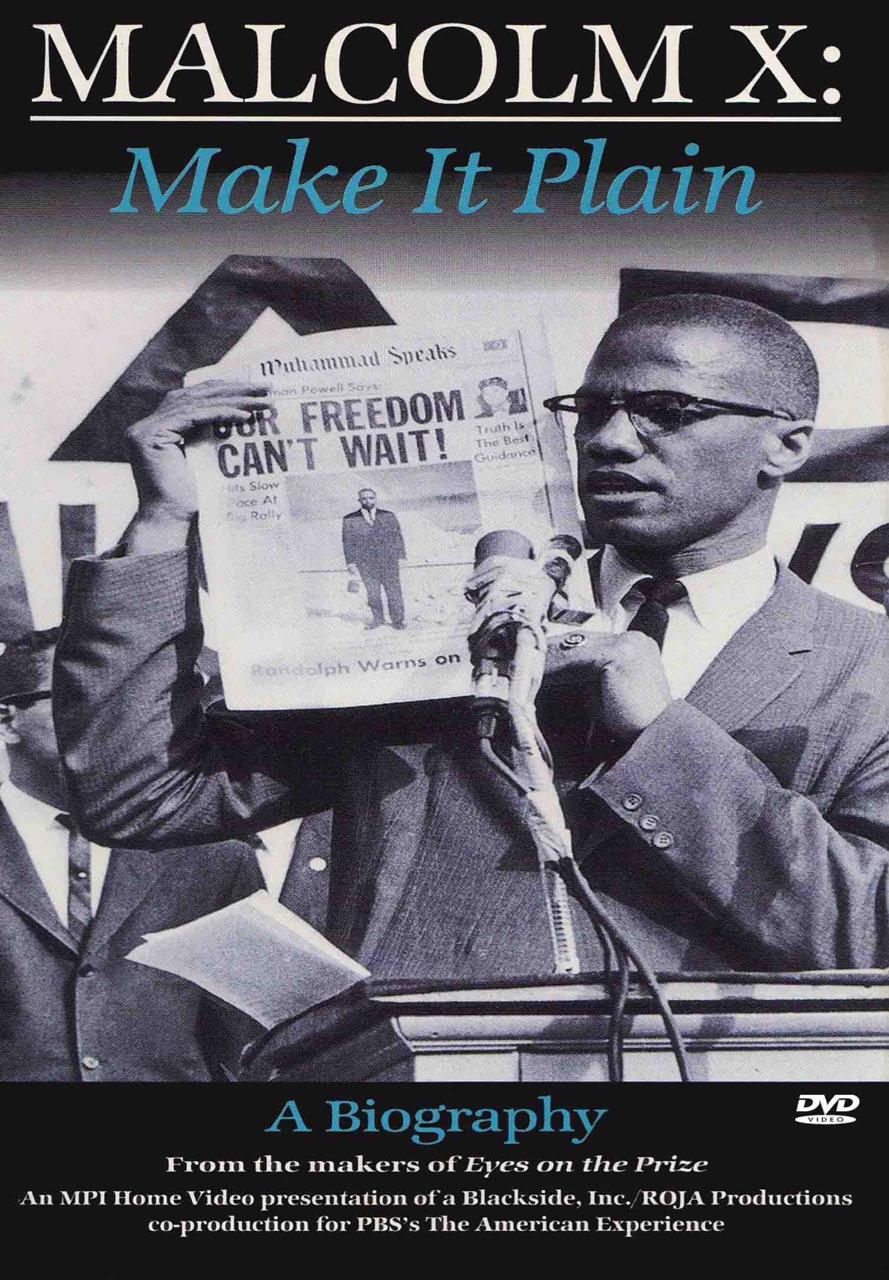

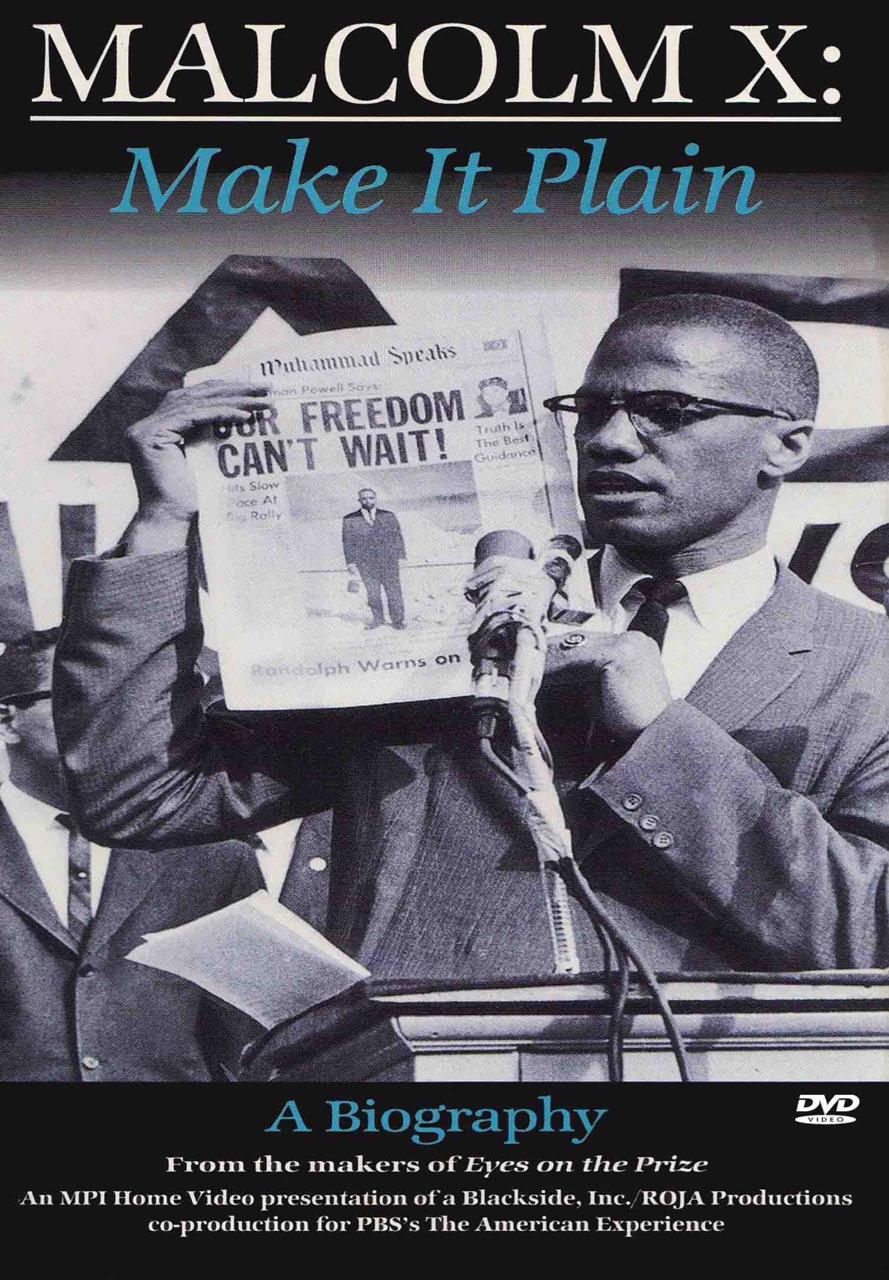

9. Malcolm X: Make It Plain – Orlando Bagwell (1994)

Smart, well-conceived, and thoroughly researched biographical account of Malcolm X–which proves to be the most authoritarian film work some 20 years later. Orlando Bagwell brilliantly captures the cultural impact, sociopolitical stance, and global legacy of the beloved yet debated activist.

Smart, well-conceived, and thoroughly researched biographical account of Malcolm X–which proves to be the most authoritarian film work some 20 years later. Orlando Bagwell brilliantly captures the cultural impact, sociopolitical stance, and global legacy of the beloved yet debated activist.

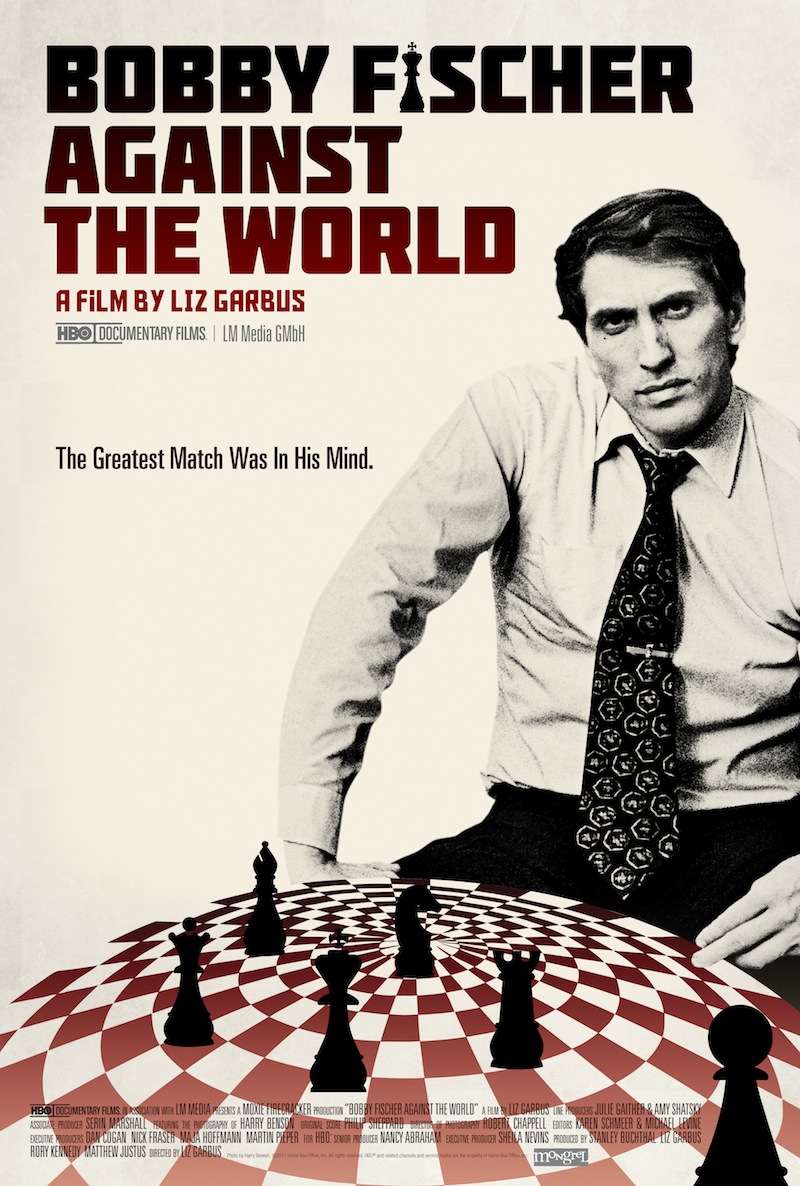

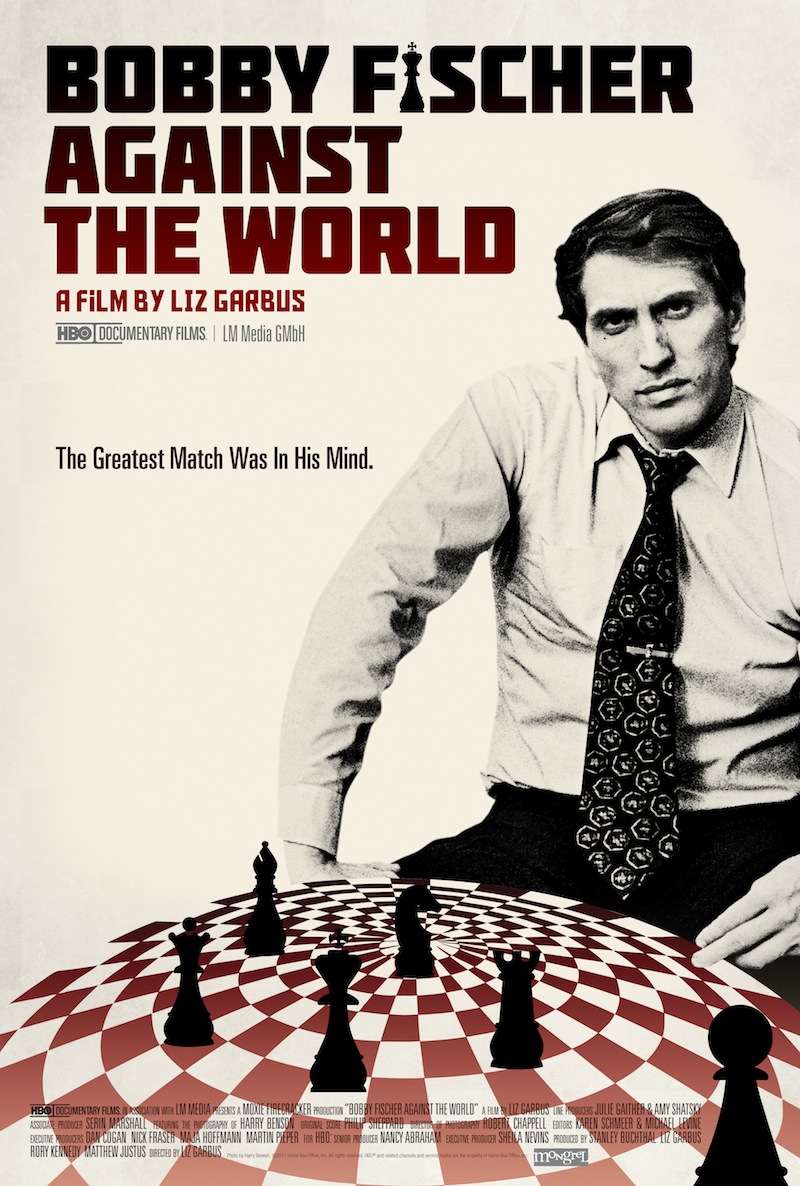

10. Bobby Fischer Against the World – Liz Garbus (2011)

Built with suspense and mystery Liz Garbus’ biographical film delivers an uncompromising look into the complexity of a chess genius. Commentary from close friends and relatives and those of the chess championship world breaks down all the nuances, convolutions, and challenges of the young and old Bobby Fischer.

Built with suspense and mystery Liz Garbus’ biographical film delivers an uncompromising look into the complexity of a chess genius. Commentary from close friends and relatives and those of the chess championship world breaks down all the nuances, convolutions, and challenges of the young and old Bobby Fischer.

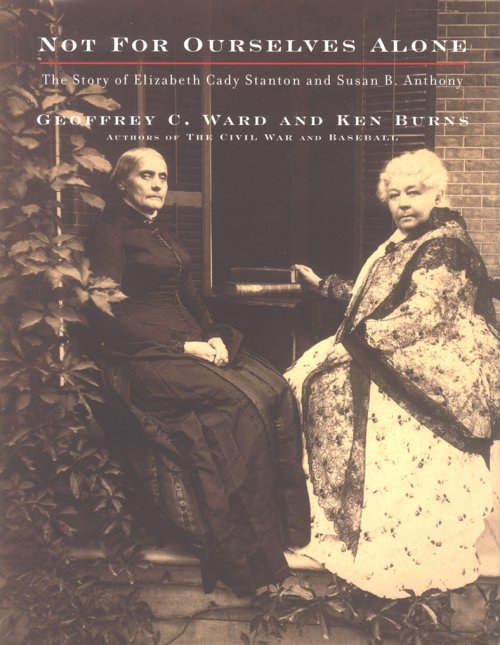

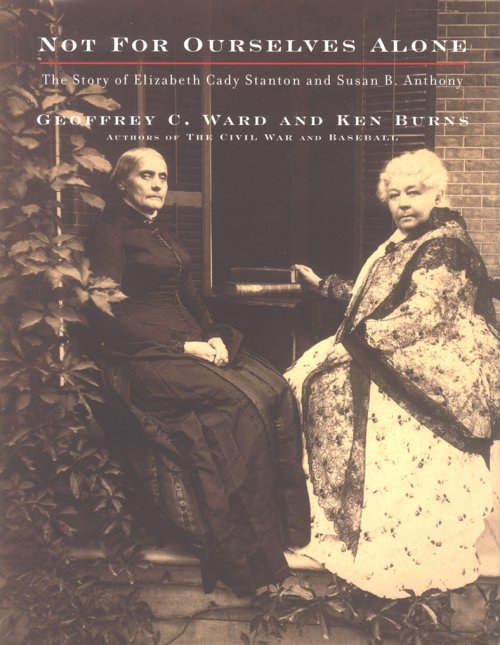

11. Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony – Ken Burns (1999)

Nothing short of the term “superb” can be added to a Ken Burns’ historic film piece. However, with this documentary he takes it up a notch while still employing the same elements that has become his signature style. This award-winning film does one of two things–one, it brilliantly articulates the American women’s suffrage movement from it’s nascent stage to it’s final denouement and two, seamlessly interweaves the biography and activist work by the two stalwarts of the movement–who ironically didn’t live to see the day U.S. women were granted the right to vote.

Nothing short of the term “superb” can be added to a Ken Burns’ historic film piece. However, with this documentary he takes it up a notch while still employing the same elements that has become his signature style. This award-winning film does one of two things–one, it brilliantly articulates the American women’s suffrage movement from it’s nascent stage to it’s final denouement and two, seamlessly interweaves the biography and activist work by the two stalwarts of the movement–who ironically didn’t live to see the day U.S. women were granted the right to vote.

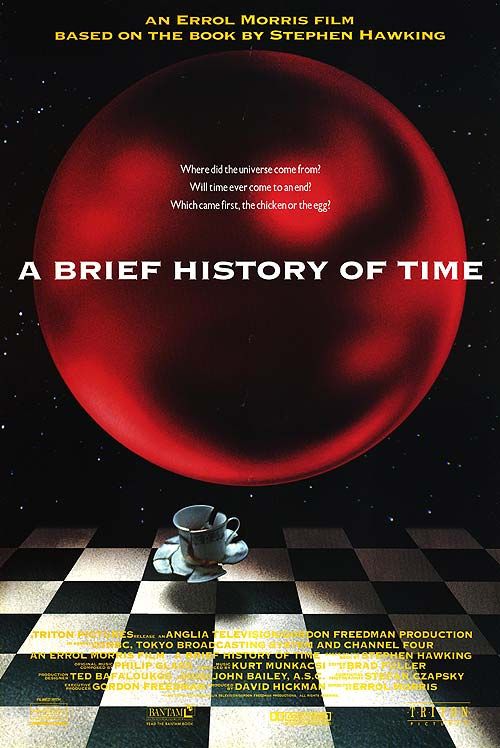

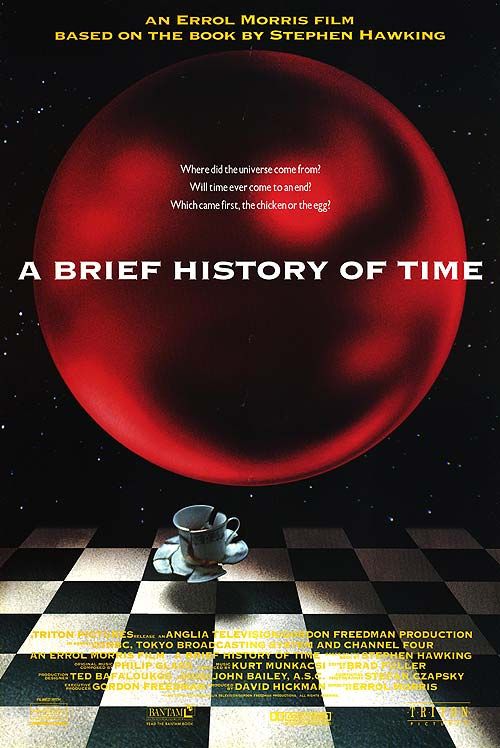

12. A Brief History of Time – Errol Morris (1992)

Not necessarily his forte in documentary film work but the illustrious Errol Morris pulls it off in this brilliant documentary film on Stephen Hawking. The dynamism of the film is the parallel element of narrating Stephen Hawking’s biography with the theories and details of his bestselling book at the time–also the film’s title. Creative visual storytelling, wonderful cinematography and the powerful use of symbolic imagery does this film very well.

Not necessarily his forte in documentary film work but the illustrious Errol Morris pulls it off in this brilliant documentary film on Stephen Hawking. The dynamism of the film is the parallel element of narrating Stephen Hawking’s biography with the theories and details of his bestselling book at the time–also the film’s title. Creative visual storytelling, wonderful cinematography and the powerful use of symbolic imagery does this film very well.

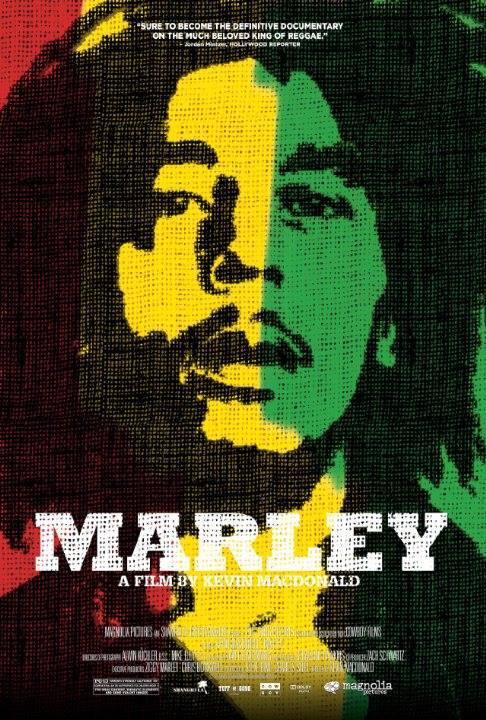

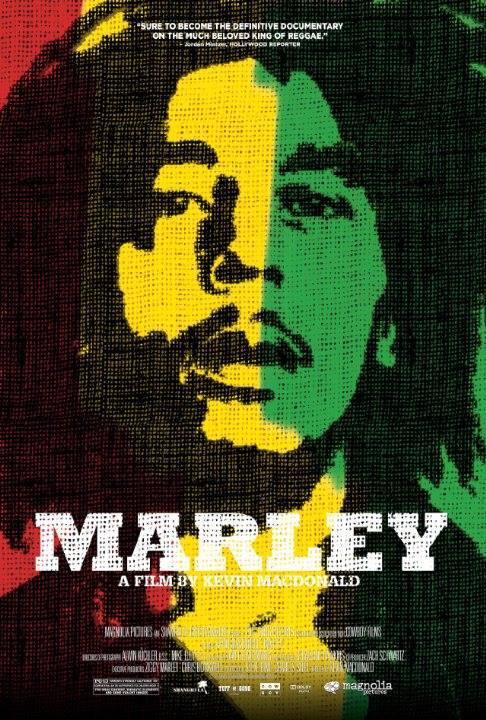

13. Marley – Kevin Macdonald (2012)

Powerful biographical documentary that reveals the other side of the story of the Jamaican music legend with all his faults. With never-before-seen footage coupled with never-before-heard songs Kevin MacDonald delivers a personable story of Bob Marley far from a homage or tribute film.

Powerful biographical documentary that reveals the other side of the story of the Jamaican music legend with all his faults. With never-before-seen footage coupled with never-before-heard songs Kevin MacDonald delivers a personable story of Bob Marley far from a homage or tribute film.

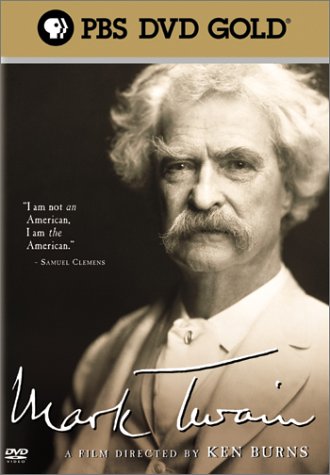

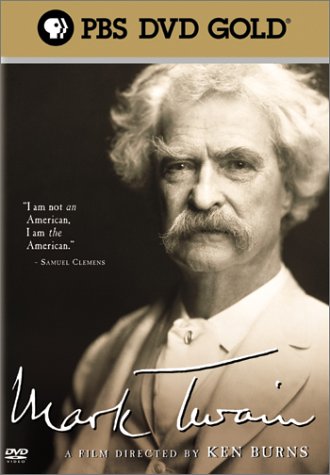

14. Mark Twain – Ken Burns (2001)

Ken Burns in his uniquely signature style brings to life the emotion, accomplishment, loss, frustration, and culture impact of the celebrated writer to viewers. In an amazing fashion of a biographic film portrait Burns is able to parallel themes of the writer’s life with that of 19th century American history.

Ken Burns in his uniquely signature style brings to life the emotion, accomplishment, loss, frustration, and culture impact of the celebrated writer to viewers. In an amazing fashion of a biographic film portrait Burns is able to parallel themes of the writer’s life with that of 19th century American history.

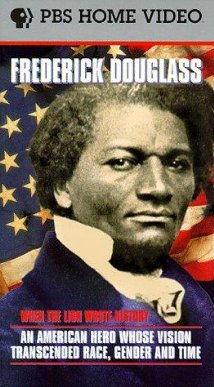

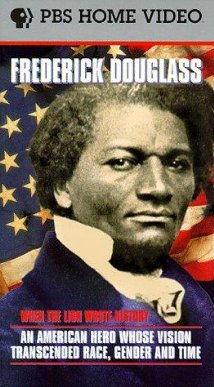

15. Frederick Douglas: When The Lion Wrote History – Orlando Bagwell (1994)

An authoritative, biographical film on the first African-American impact activist in United States history. Thoroughly investigative and researched into the early life and career span of the elegant orator and provocative abolitionist. Nothing falls short in this film that assays Douglass’ life and work.

An authoritative, biographical film on the first African-American impact activist in United States history. Thoroughly investigative and researched into the early life and career span of the elegant orator and provocative abolitionist. Nothing falls short in this film that assays Douglass’ life and work.

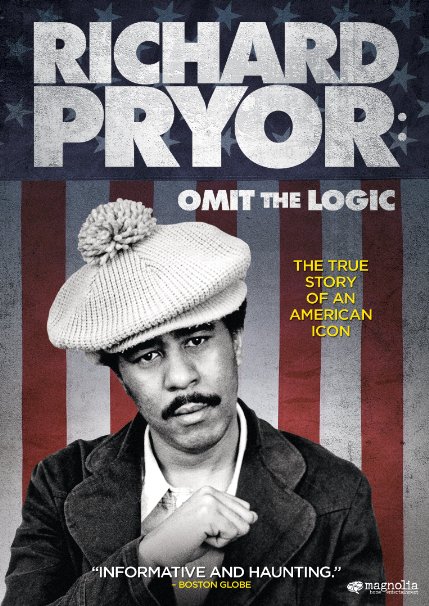

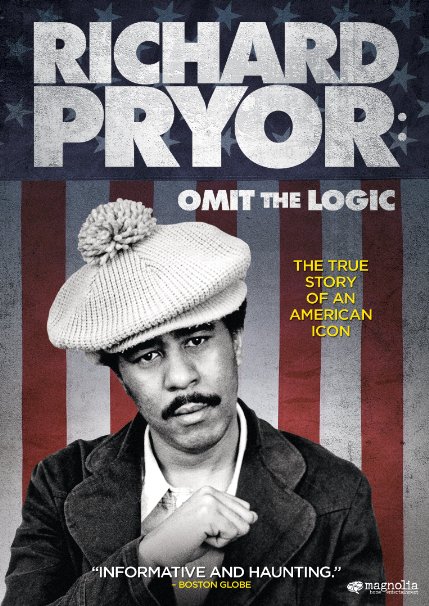

16. Richard Pryor: Omit the Logic – Marina Zenovich (2013)

Emotionally-driven and humorously-charged this documentary film brings to life the magnetic appeal and power of Richard Pryor–considered to be the best comic of his time. The director takes us into the life and nuances of Pryor’s life and the headline stories that drove it.

Emotionally-driven and humorously-charged this documentary film brings to life the magnetic appeal and power of Richard Pryor–considered to be the best comic of his time. The director takes us into the life and nuances of Pryor’s life and the headline stories that drove it.

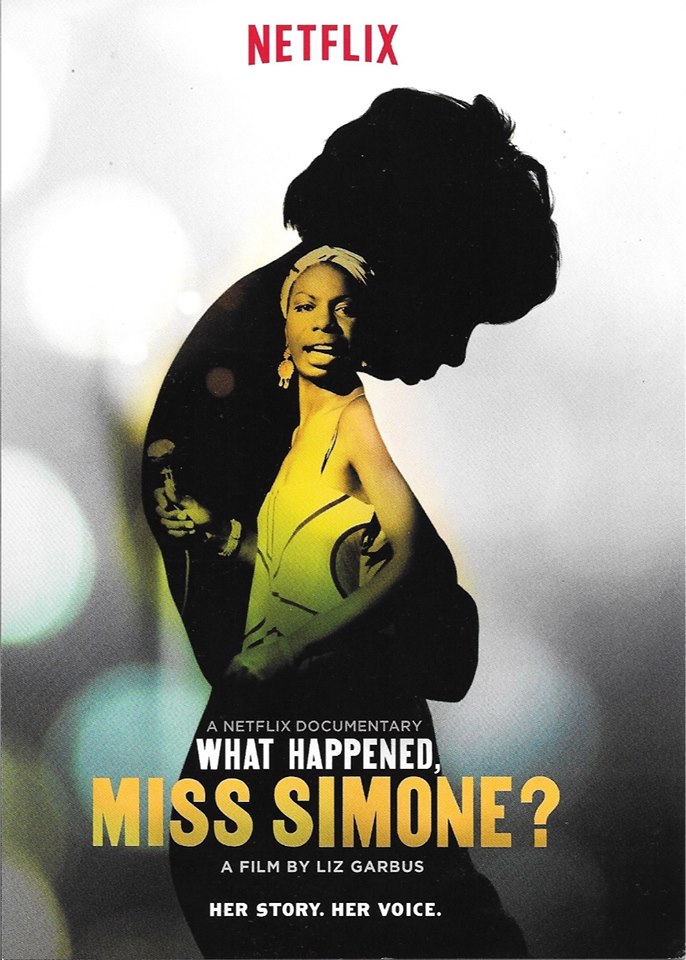

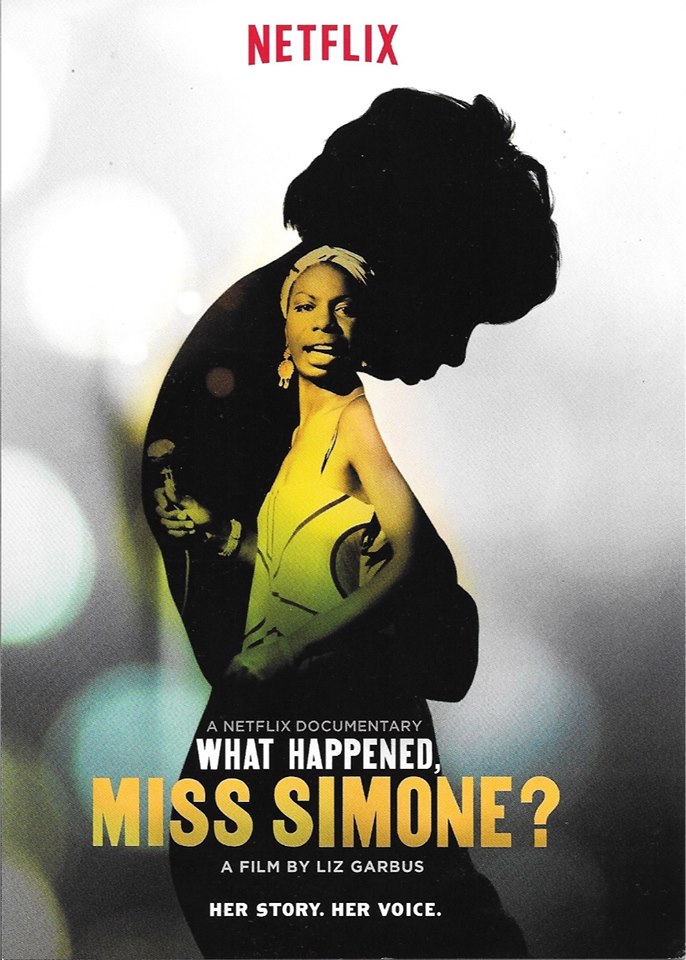

17. What Happened, Miss Simone? – Liz Garbus (2015)

Liz Garbus does not fall short nor shy away from the dynamism of Nina Simone’s character and life story. Her activist work and political commentary that tied so heavily into her brilliant musical work is portrayed profoundly in this engaging film.

Liz Garbus does not fall short nor shy away from the dynamism of Nina Simone’s character and life story. Her activist work and political commentary that tied so heavily into her brilliant musical work is portrayed profoundly in this engaging film.

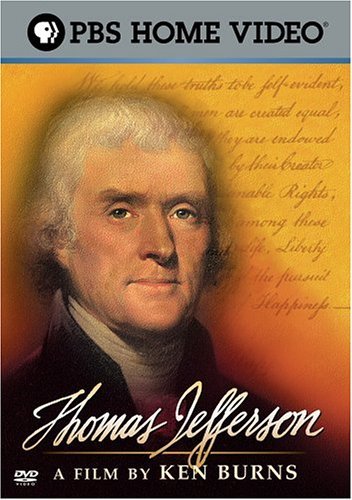

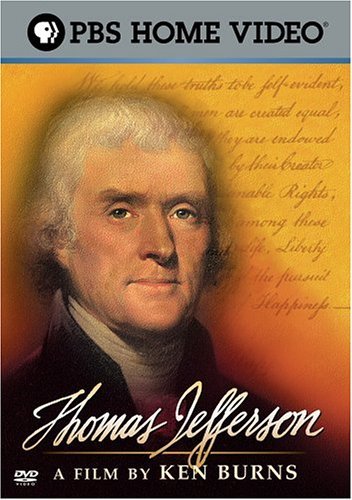

18. Thomas Jefferson – Ken Burns (1996)

Another astounding historical and biographical documentary of a renowned filmmaker in a class of his own. Again–to his credit Ken Burns interweaves the accomplishment and legacy of an important figure in early U.S. history while detailing the most important events of the times.

Another astounding historical and biographical documentary of a renowned filmmaker in a class of his own. Again–to his credit Ken Burns interweaves the accomplishment and legacy of an important figure in early U.S. history while detailing the most important events of the times.

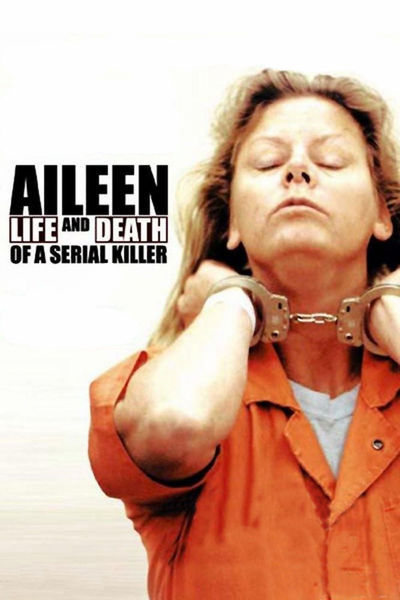

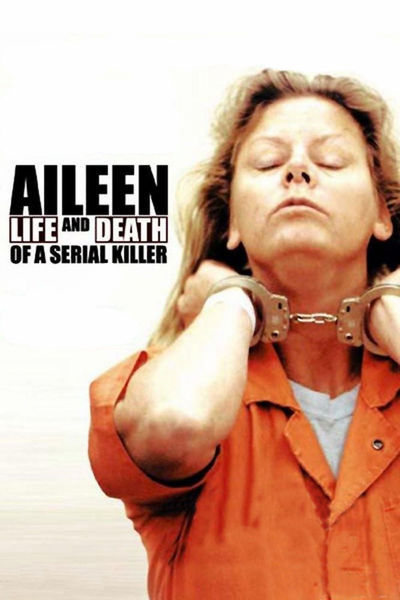

19. Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer – Nick Broomfield (2003)

A vividly and chilling biographical portrait of serial killer Aileen Wuornos from her rough childhood upbringing to her state execution. Although this was a follow-up to an earlier documentary film on her Nick Broomfield employs his best auteur style in his repertoire–cinéma vérité and captures engagingly the life, mind, and behavior of a mentally-ill prostitute-turned-murderer.

A vividly and chilling biographical portrait of serial killer Aileen Wuornos from her rough childhood upbringing to her state execution. Although this was a follow-up to an earlier documentary film on her Nick Broomfield employs his best auteur style in his repertoire–cinéma vérité and captures engagingly the life, mind, and behavior of a mentally-ill prostitute-turned-murderer.

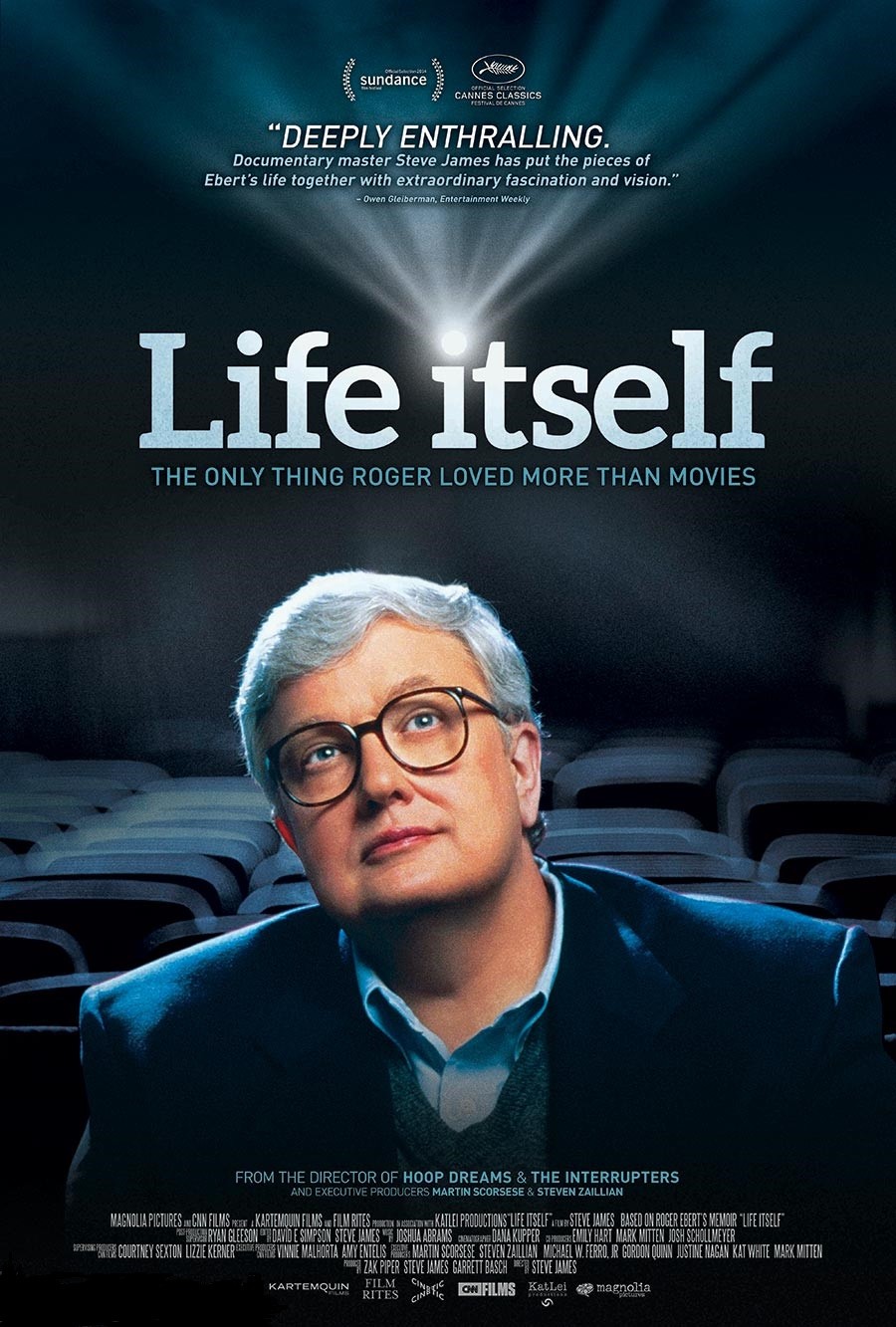

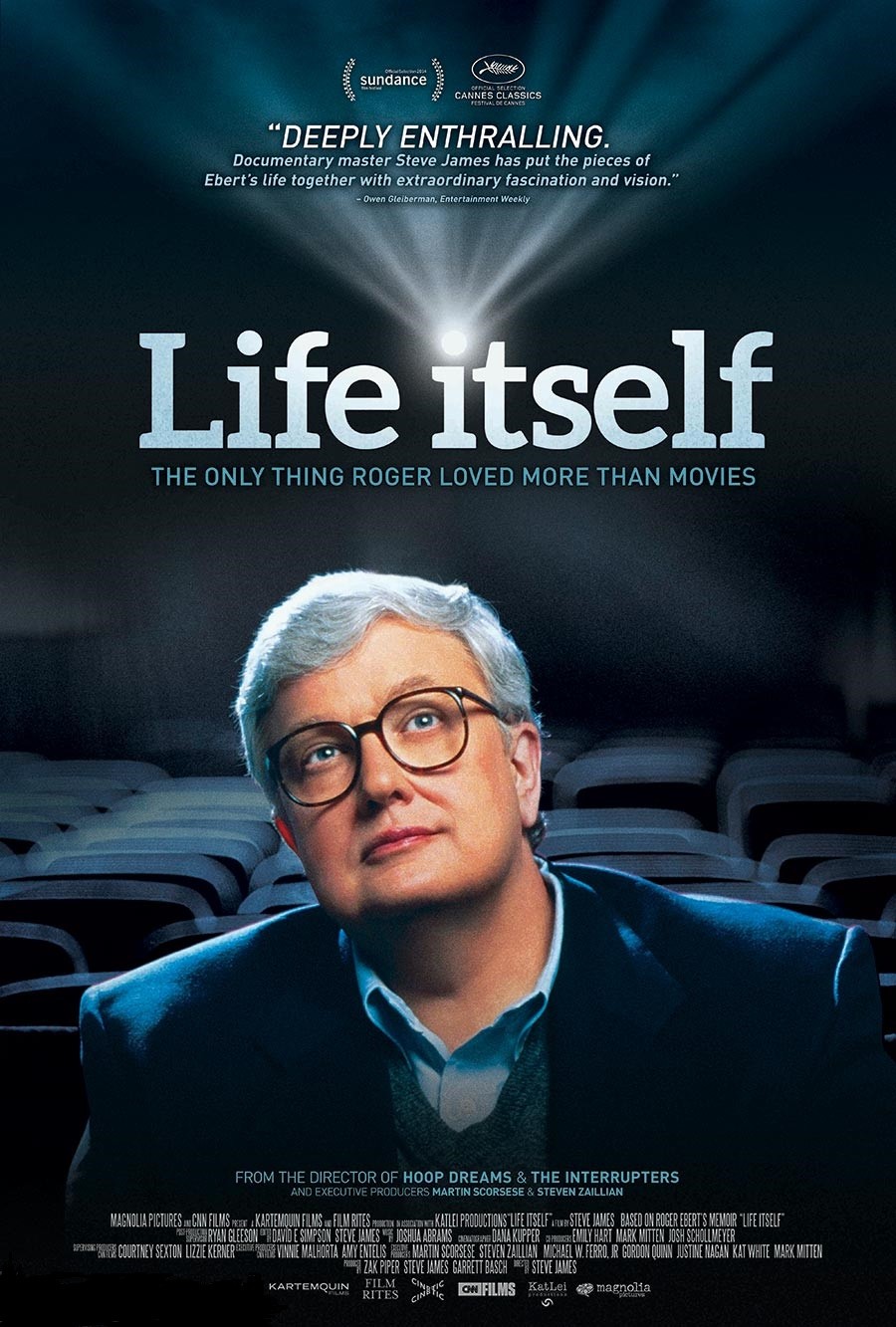

20. Life Itself – Steve James (2014)

Touching, tribute-esque film portrait of the legendary film critic. Timely to the end of Roger Ebert’s own death, this film carries profoundly the lasting impact Rogert Ebert had on movie audiences for generations and the unique mark unto himself he had on Hollywood.

Touching, tribute-esque film portrait of the legendary film critic. Timely to the end of Roger Ebert’s own death, this film carries profoundly the lasting impact Rogert Ebert had on movie audiences for generations and the unique mark unto himself he had on Hollywood.

NOTEABLE SNUBS:

Maynard – Samuel Pollard (2017)

Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine – Alex Gibney (2015)

Quincy – Alan Hicks & Rashida Jones (2018)

The Beatles Anthology – Geoff Wonfor and Bob Smeaton (1995)

Whitney – Kevin Macdonald (2018)

Runnin’ Down a Dream – Peter Bogdanovich (2007)

Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool – Stanley Nelson (2019)

Thelonious Monk: Straight, No Chaser – Charlotte Zwerin (1988)

Andy Warhol: A Documentary Film – Ric Burns (2006)

Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown – Alex Gibney (2014)

RBG – Julie Cohen & Betsy West (2018)

Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold – Griffin Dunne (2017)

The Best That Never Was – Jonathan Hock (2010)

Jane – Brett Morgen (2017)

Grace Jones: Blood Light and Bami – Sophie Fiennes (2017)

Pavarotti – Ron Howard (2019)

Benji – Coodie and Chike (2012)

Frank Lloyd Wright – Ken Burns (1998)

Fela Kuti: Music Is the Weapon – Jean-Jacques Flori and Stéphane Tchalgadjieff (1982)

You Don’t Know Bo – Michael Bonfiglio (2012)

Pope Francis: A Man of His Word – Wim Wenders (2018)

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? – Morgan Neville (2018)

The Gospel According to Andre – Kate Novack (2017)

Big Shot – Kevin Connolly (2013)

Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am – Timothy Greenfield-Sanders (2019)

Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson – Ken Burns (2005)

Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck – Brett Morgen (2015)